Virtual Private Realms

-

April 19, 2021

March 19, 2021

Lananh Le

Din Sama

Nguyễn Đức Huy

mi-mimi

Nghĩa Đặng

Trịnh Cẩm Nhi

Hà Ninh

The exhibition 'Virtual Private Realms’ brings together the works of 7 artists: Lananh Le, Din Sama, Nguyễn Đức Huy, mi-mimi, Nghĩa Đặng, Trịnh Cẩm Nhi, and Hà Ninh, with a focus on their painting practice.

Belonging to the 9X (millennial) generation, these artists have contributed to a new wave of practitioners in the Vietnamese art scene. The works in the exhibition, while diverse in style, still share similarities in their visual lexicon: from the use of highly personalized symbols, a dismissive attitude towards macro-narratives, an arrangement of virtual spaces, to a layering of complicated psychological flows - all of which have been flattened, projected, and pinned down on the surface of paintings.

‘Virtual Private Realms' mostly introduces the artists' most recent creations, coupled with experimentation that expand the boundaries of paper, canvas, the act of drawing, and other fundamental elements that constitute the language of painting.

This exhibition is organised by Manzi Art Space with support from the Goethe Institut, British Council Vietnam and MoT+++.

ARTWORKS

GALLERY

Curatorial Essay _ by Vân Đỗ & Hà Ninh

###

fishbowl-like simulacrum of an inner world containing fragments of personal memory, hybrid animals, dream imagery, wondrous geometry reflecting a state of mind..."

Excerpt from Lananh Le’s statement for the digital painting series in the exhibition ‘frozen data’ (MọT+++, 2020)

Perhaps it would be fitting to enter the ‘virtual private realm’ of this exhibition through the surreal, ghostly, and immaterial world of Lananh Le. To peer into the mind of this artist friend, whom we missed the chance to meet in real life, we can only rely on images scattered on the Internet or a few exchanges preserved by others from semi-intimate conversations with Lananh. But the most poignant pieces would be the memories retold by Lananh’s friends, those who have spent a part of their lives with her. Lananh usually inundates her ‘canvas’ with unexpected subconscious outbursts. Unpolished and without meticulous calculations of meaning or composition, the symbols in her works resemble oracles from a dream. Fantastic combination of irregular visual choices that constantly shift — objects of dense cultural meanings (chandelier, altar, temples, and bursts), animals that step out from the wilderness (tiger, zebra, lizard, varan, and snake), peculiar brush strokes (that depict faces—both familiar and strange, or a deity that manifests from squiggly lines on grid paper), the symbols in her works function like a kaleidoscope. To convert, categorize, or impose a foreign system (usually language-based) onto these symbols seems to diminish their own sacredness, since they themselves exude a condensed ambience of chaos – a synthesized world swirling and tantalizing in darkness that refuses any explanation. In this exhibition, we are fortunate to be able

to introduce safari (2019) and guanyin (2019), from the series of digital paintings that Lananh once showed at her solo exhibition ‘frozen data’ at MoT+++ in early 2020. While still in pursuit of mental waves that ebb and flow without regulation, her handling of the works in this exhibition somewhat diverged from her usual spontaneous techniques in oil painting, which she juggled with the materials physically on her canvas. Lananh gathered a myriad of materials (photographs, sketches in pencil/pen, watercolor, and oil

paint), then cast a digital spell to layer and hybridize them using Photoshop. The end result is a moving-image piece that continues to palpate through a projector, undulating with the exhibition’s opening-closing rhythm. The life of Lananh’s works, thus, perpetually exists in between two states: awake - asleep.

In a similar mode of ‘personal myth-making’ is Hà Ninh’s

world of maps. Hà Ninh utilizes one of the most mechanical

techniques of painting - mark-making/drawing. Yet, in contrast to Lananh, Hà Ninh constructed a world crisscrossed with rules and standards, backed by a complicated lexicon. That world harbors a history (its own past), with its foundation embedded in his long-term project called ‘My Land’. This is one of the most significant projects with which to embark on that journey for those who are interested in exploring Hà Ninh’s art world. While studying abroad in the USA in 2017 and caught in the chaotic snare of cultural clash and conflicting ideologies, Hà Ninh poured all of his efforts into building ‘My Land’ with the end purpose of having absolute autonomy in the real world, which he felt as if he had limited decision-making power. ‘My Land’ begins with an arbitrary statement: this territory bears no resemblance to any human culture; thus, all standard paradigms in said world will be self-referential and only make sense within the boundaries of its imagined landscape. The exhibition showcases [mothermap], the backbone of ‘My Land’, which acts as a compass, guiding the viewers through Hà Ninh’s labyrinth. [mothermap] is updated annually by the artist, partially reflecting the artist’s psychological unfolding and changing perspective during his own transitional periods.

Compared to the 2019 version, [mothermap]’s 2020 iteration marks the shift in landscape construction: from a more logical calculation to a more organic approach. The sky and water have merged, allowing the stars to “swim” freely and deeply into continents, creating an abundance of skyline in each location. Looking at the most updated [mothermap] is akin to participating in a surgery, where the 8x8 grid system is no longer clearly visible, but rather faint points of reference that suggest the relative location of each construction - now transformed into bodily organs. As Hà Ninh shared, this gradual departure from logical reasoning to move toward a more instinctual connection with the work is, in itself a self-soothing process to handle loneliness and human fragility against the infiniteness of space and time.

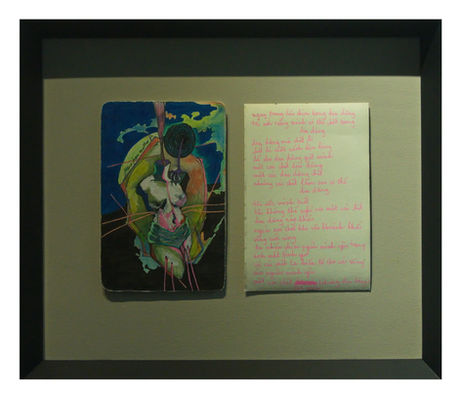

While Hà Ninh and Lananh set up a world densely packed with symbols, Nghĩa Đặng chooses a more condensed and succinct method to codify symbols and include narratives into a pair of paintings not too far (2020) and what’s too far (2020). The two paintings are drawn with charcoal on paper, one of the fundamental materials of painting, with references to conceptual prototypes - one of the artist’s foci in his practice. Here, two prototypes are present: a pair of bulls and what the artist calls ‘father-thing’(*)

---

(*) According to the artist, ‘father-thing’, a word borrowed from philosopher Slavoj Žižek and psychotherapist Sigmund Freud, is a purely visual existence that is hard to explain. ‘Father-thing’ stems from the subconscious, or an illogical reproduction of dreamlike or fear-induced images. Žižek used ‘father-thing’ in his book ‘The Plague of Fantasies’, alluding to the desire for complete control as well as Oedipus complex,

feeling of guilt, and the dominant tendency of the masculinity embodied by the paternal figure, where he is seen as a phantom that imposes himself upon external subjects such as the mother or the son

---

Upon closer look, we are hit with the feelings that things are not the way they seem. At the center of not too far, a scene where a female bull is nursing its cub, seems to reveal another primal aspect; the lush greenery, which creates the illusion of ancient forest, is in fact indoor plants (banana-leaf pothos, snake plant, pencil cactus, etc.). Even the paper canvas, seemingly intact, is actually a collage of paper units, a remnant of a stream-of-consciousness experiment with piecing apart - binding together. The illusion of an ‘outside world’ continues eluding the seeker, who wishes to understand, explain, and control it, since ‘the natural world’

out there is no longer nearby. Extending his private concern with construction of societal roles, as well as the continuous tug-of war between masculinity and femininity, Nghĩa Đặng “plants” an imaginary garden through intertextual practice, freely connecting his inspirations from poetry and personal memories, to archival photography and people who have cast a shadow upon his subconscious.

Trịnh Cẩm Nhi too draws inspiration from ‘nature’, the central

images of her paintings’ universe — a universe half surrealist

(reminiscent of Giorgio de Chirico) half abstract (possessing the air of Hilma af Klint) — are flowers, the female figure, and finely-sliced spaces. Fluctuating elegantly between imagination and the senses, between careful calculation and unforeseeable sensations from the physical body, Nhi timely captures the emotions that come to her. She projects her sensitive spirit, records the complex movements of the psyche, transforms them into objects, and arranges them into

the polished spaces of an eternal museum. Seemingly concealed beneath her canvas is a humble feminist perspective. With soft curves and sweetly-colored palette, the floral figures and the female body in Nhi’s paintings exude sensuality, yet it is not the sexualized sensuality where women are objects to be drawn/gazed at. The female figure in her works does not abide with anatomical ratios or conventional standards of beauty upheld by society. Regardless of whether she looks demurely at the viewers, or turns her back completely to avoid strangers’ gawk, she still proudly displays her body. Similarly, Nhi’s flowers also delicately allude to the female reproductive organs. Despite the dreamy tones, the ambience inside Trịnh Cẩm Nhi’s painting is neither romantic nor mystical: it is not a space of obsession, but rather one of uncertain narratives spun by a calm storyteller. There exists a natural confidence in the way Nhi works with spaces that are disturbed, disjointed, splintered, and